Editor’s Note: This post is part of our series on marker bills and the 2018 Farm Bill. You can track the farm bill’s progress through Congress here and elsewhere on this blog.

Farmers face a uniquely high amount of risk. An unexpected drought, an influx of pests, or a lower than expected crop yield can all have devastating effects on a farmer’s livelihood. Even unexpectedly good weather and high crop yields can harm farmers by creating a glut that drives down prices.

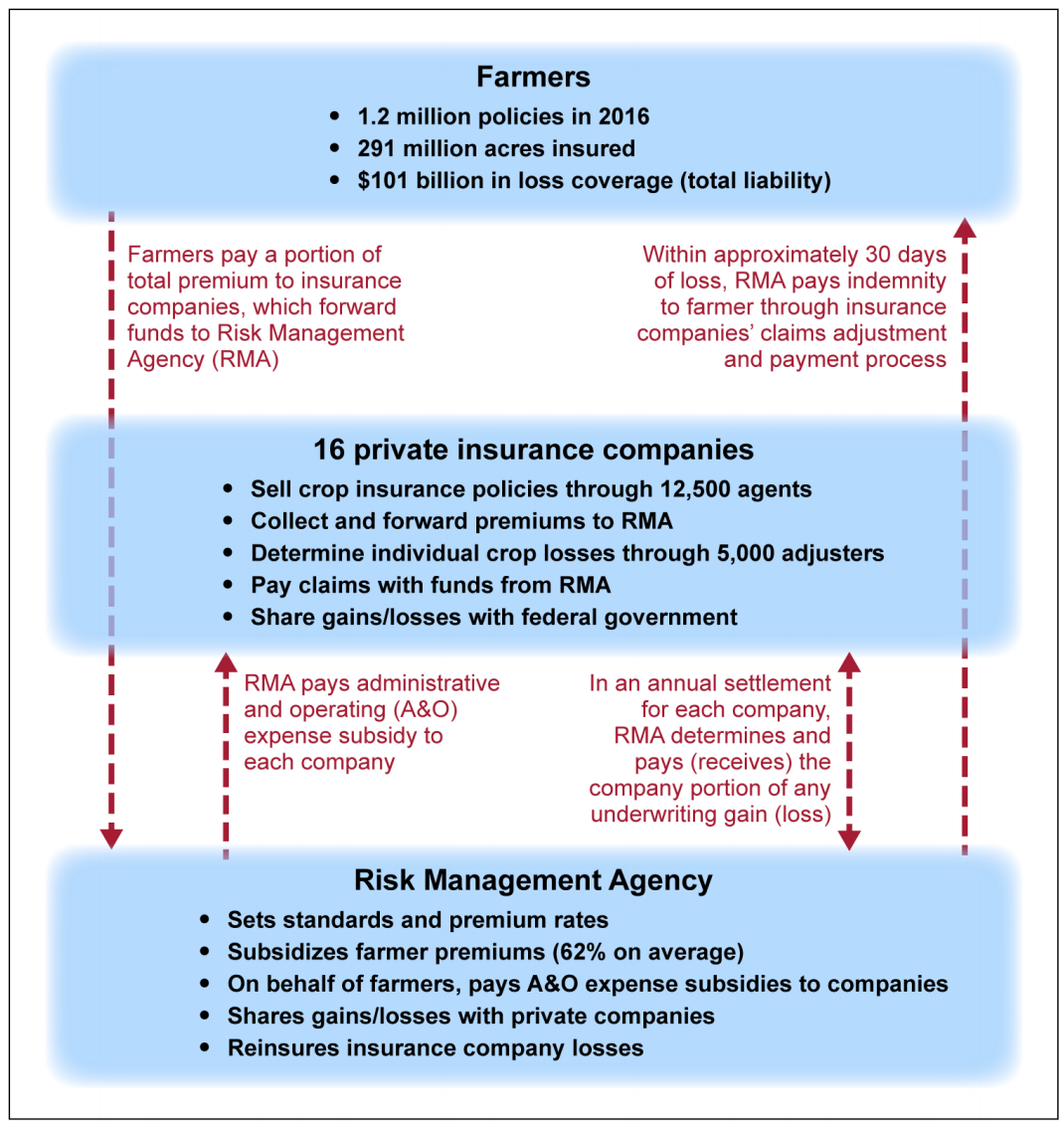

To help farmers manage this risk, the government subsidizes crop insurance premiums. This federal crop insurance program is periodically updated in the farm bill, and it subsidizes over 60% of all premiums farmers pay for their crop insurance. Overall, this has been an extremely beneficial program for American farmers. However, much of the federal funding behind the crop insurance program has been wasted on misplaced priorities and on farmers who simply do not need public support.

Criticism over this waste has been growing over the years, and a bipartisan group in Congress recently set out to improve the crop insurance program with legislation called the Assisting Family Farmers through Insurance Reform Measures Act (or the AFFIRM Act).

There are three major flaws with federal crop insurance — flaws that the AFFIRM Act addresses head on.

First, there is no means test for who receives crop insurance subsidies. This enables farmers making over a million dollars a year to receive taxpayer support for their insurance premiums. This is money these farmers simply do not need — and it is a revenue guarantee that the United States would never give to any other private business. Indeed, every other major subsidy program within the farm bill itself has restrictions based on the annual gross income of the farmer. For example, commodity programs, which directly subsidize certain crops such as corn and wheat, bar any farmers with adjusted gross incomes over $750,000 from receiving public support. Crop insurance subsidies need similar limitations.

Some argue that means testing crop insurance will cause the wealthiest farmers to stop purchasing insurance, and thus create a “death spiral” in the market. However, crop insurance is usually necessary for everyone given the unavoidable external risk factors in agriculture. Some of this behavior could also be barred by anti-competitive laws. Therefore, the necessary condition for this fear is unlikely to occur from means testing subsidies. To the extent that legitimate market behavior did eventually lead to an unsustainable amount of insurance dropouts from wealthy farmers, USDA could correct this through an insurance mandate or additional subsidies for middle-income farms.

Second, the federal crop insurance program creates artificial and bizarre incentives through enabling farmers to collect insurance money that can exceed what they would make on the free market. This inefficiency is created through a “Harvest Price Option” that gives farmers insurance payouts based on the price of their crops at harvest, as opposed to planting time. Because crop prices often fluctuate dramatically in this time period, it allows farmers to receive far more money through their insurance payments than they expected when they planted their crops. The purpose of insurance, however, is to put someone in the same position they would have been in absent unexpected event. No one receives a Cadillac when they total their Dodge Neon. Yet this is essentially what we are giving farmers through the harvest price option of the federal crop insurance program.

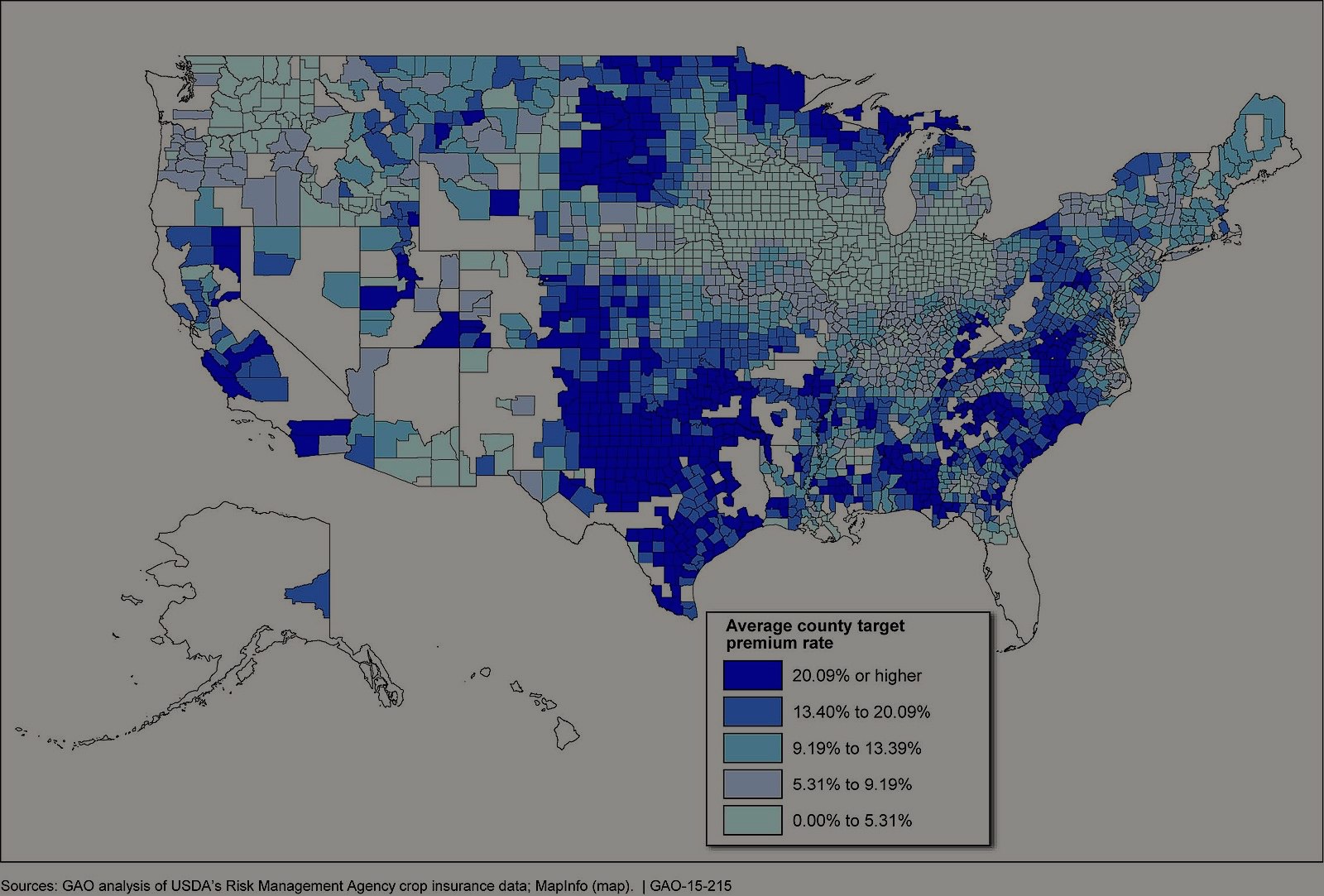

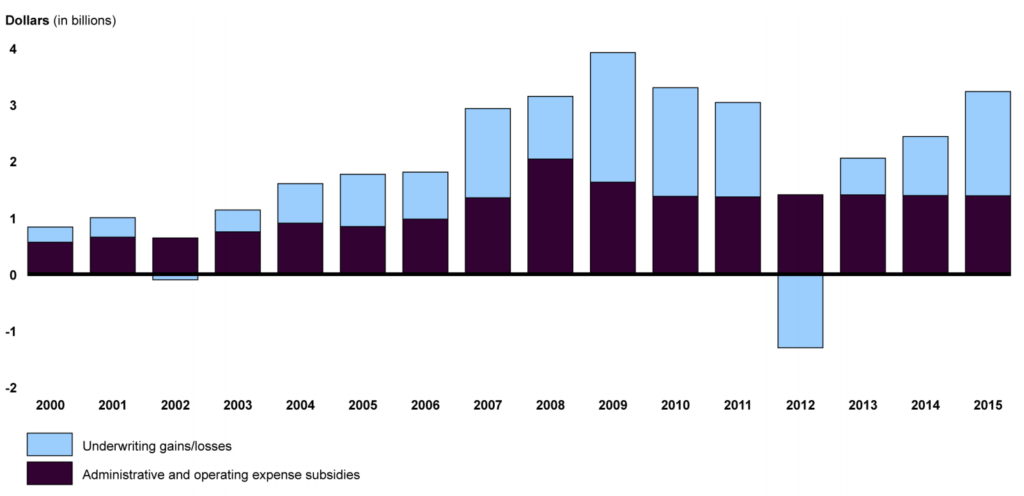

Third, the federal crop insurance program funnels billions of dollars in profits to financial companies. Indeed, the federal crop insurance program guarantees a target return of 14.5% for participating private insurers. This return is far higher return than the “average reasonable rate” of 9.6%. And it is a guarantee that is not necessary for financial companies to participate in crop insurance.

Administrative and Operating (A&O) Expense Subsidies and Underwriting Gains Paid to Insurance Companies, 2000 through 2015. Source: Government Accountability Office. through 2015.

Thankfully, the bipartisan AFFIRM act has been introduced in Congress to address all of these issues. It bars subsidies to farmers with adjusted gross incomes above $250,000, and it caps the total amount of premiums any one entity can receive at $40,000. It eliminates the harvest price option to ensure that no farmer can manipulate their insurance to receive windfall payments, and it finally sets the target rate of return on crop insurance rates to the sensible rate of 8.9%.

As Senator Jeff Flake put it when he introduced the AFFIRM Act: “My bipartisan plan for the next farm bill will put $30 billion back in the pockets of small farmers and taxpayers at large, and it will do that by going after some of Big Ag’s most egregious handouts, carve-outs, and subsidies.”

The AFFIRM act offers real, bipartisan solutions to the growing problem of wasteful spending and mistaken priorities in the farm bill. The Farm Bill Law Enterprise supports the changes proposed the AFFIRM Act, and we made similar recommendations in our report titled Productivity and Risk Management. It is time to be smart about how we can truly help farmers in America. An end to millionaire subsidies, Wall Street handouts, and windfall insurance awards seems like a pretty good place to start.